Twigs litter the moist footpath. They have fallen from the many, many trees that are everywhere. A few metres ahead, a river bursts into view, its gentle whistle suddenly becoming a loud rustle. Apart from the sound of her feet crushing the dry leaves beneath and the river’s roar, Vivi can’t hear any other sound.

The chirp of the birds is lost to her ears although birds are nesting in the trees that are staring down at her. Among them is the Dzanga robin, the little colourful bird that can only be found here and nowhere else in the world. As she stares at the rare robin’s bright yellow belly, Vivi has no idea that this bird can only be found here in her forest.

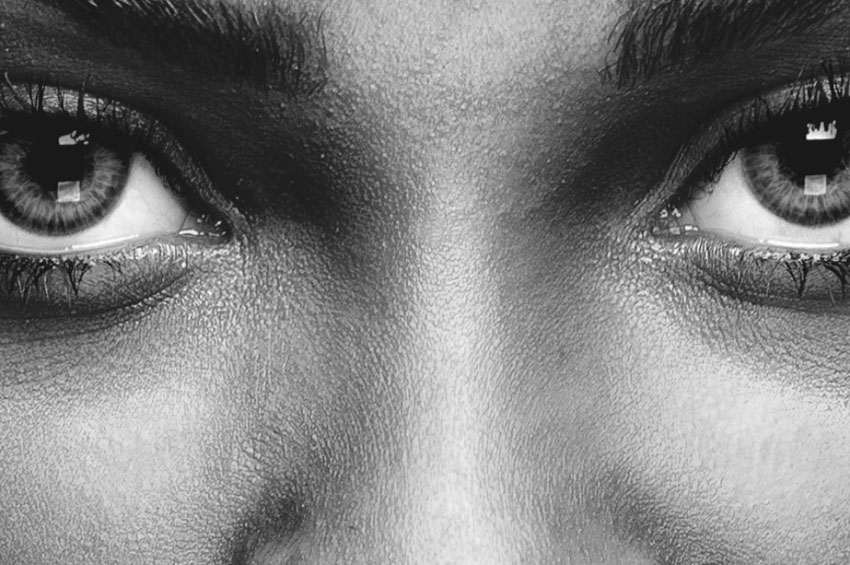

Her hair is short, her eyes brown. Her complexion shares the same colour with the ebony tree she is leaning against. The celebrated tree is so huge that its trunk can easily fit five versions of Vivi. Such trees are a major reason why forestry is the second leading employer in Central Africa Republic, behind only the government.

"The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge." Bertrand Russell

A few metres away are several African tulip trees. Their bright orange flowers are one of Vivi’s favourite forest sights. A stone throw away from the tulip trees is yet another favourite sight that always captivates her.

About one hundred elephants are stumping at Dzanga Bai, a marshy clearing in Dzanga Sanga rainforest. They seem to be having a jolly good time as they swing their trunks in the moist air and stump around. Patches of mud are plastered all over many elephants, a result of the mud bathing that they love to indulge in. A mother chases her muddy calf. Catch me if you can! The baby dares mama before stumbling in the slippery mud.

There are several big guys whose sheer size gives them an air of invincibility as they stroll along majestically. Their massive ears are flapping back and forth, as if swaying to some invisible rhythm that only the giant elephants can hear. But much grander is the Dzanga Sanga rainforest that surrounds the marshy clearing where the gang of elephants is having a morning party.

On May 6th and 7th 2013, the joie de vivre of the forest elephants was shattered by the sound of bullets as Sudanese poachers stormed Dzanga bai and slaughtered at least 26 elephants.

Photo by Rudy and Peter Skitterians

When Vivi’s father told his daughter about the unprecedented slaughter, she broke down. Although she is from the nearby Bayanga village, she has never really been to the Dzanga bai clearing that elephants, bongo antelopes, forest buffaloes and other wildlife love to hang out at. But her father has told her so much about the forest and its creatures that she feels like she knows it intimately.

Dzanga Sanga is such a biodiversity hotspot that it should be attracting millions of eco-tourists and not dozens of deranged poachers. It’s a magical place that should put lots of bread on the table of Vivi’s dad and all other people who live adjacent to it.

As little Vivi cried for the slain elephants, she could have been crying for the unexploited potential of this vast Dzamba sanga rainforest. Potential that lies in ensuring that it remains a secure refuge for the wildlife and a providence basket for the local people.

This potential remains largely untapped. Partly due to unequal historical global dynamics that greatly disadvantaged many African countries. Thomas Sankara, the transformative president of Burkina Faso touched on such dynamics when he said in October 1983 that, ‘to state it more clearly, we buy more from abroad than we sell. An economy that functions on such a basis is headed for increasing ruin and catastrophe.’

But also, Vivi’s past and future remain mired in poverty because many African leaders have had the bizarre habit of shooting their continent in the foot.

The United Nation Development Programme’s 2014 Human Development Index ranks Central Africa Republic in the 185th slot. Pourquoi? Why?

République centrafricaine as Central Africa is known in French, is almost three times the size of Netherlands. But its Gross National Income is 116,000 times smaller than Netherlands. Tragic as this fact is, the bigger tragedy is a widespread acceptance by many African leaders of this as normal. But the even bigger tragedy would be for Vivi to grow up accepting her poverty plight as normal.

Vivi lives next to one of the world’s most incredible biodiversity hotspots. This proximity to natural wealth should translate to a measure of wealth for her family.

Vivi adores the bright flowers of the African tulip tree. The bright future that these flowers symbolize should not remain in the distant future.