The warm Mediterranean waters slapped my feet as the cool sea breeze soothed my weary soul.

Just being there on the humid shores of the Mediterranean, had cost me almost $2000, which was the sum total of my life’s savings, sale of a plot inherited from my mother and a debt of $500 obtained from a loan shark.

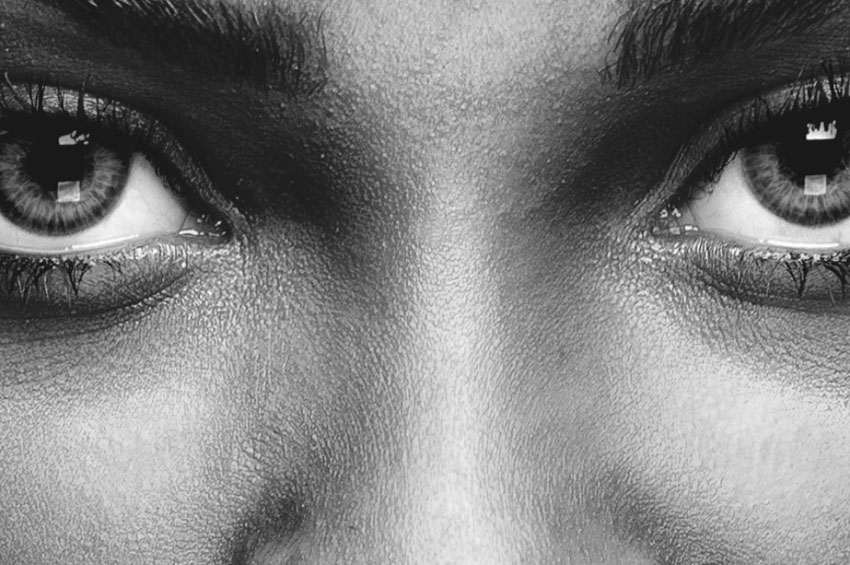

Have I bought survival or death? This question kept tugging at my heart like a restless child. I searched the vast waters momentarily intrigued by the dancing waves that would carry me all the way to Europe.

Have I bought survival or death? This question surfaced again. But I pushed it aside, in the same manner that a mother quiets a nagging child. Next to me was a woman old enough to be my mother, or even my grandmother. It was hard to tell the age represented in her excited eyes and unsmiling face that was partially covered by a blue veil.

It seemed to me that there were almost as many women as men on that hot sea shore. People appeared to be both excited and hopeless, which was an exact replica of my own emotions. I knew that hundreds of other migrants had died in this unforgiving waters of the Mediterranean. But when my best friend back in Abidjan pointed out this to me numerous times, I had always retorted that, ‘planes crash from the sky all the time but people keep boarding them.’

I smiled as my thoughts took me back to Abidjan where my journey had started. Despite its daily struggles, my country was my home and as Bwak the Bantu poet says, ‘home is like saliva, it remains in your mouth even when you spit it out.’

For weeks, the normal daily routine of my life had belied the immense excitement within.

As I hang my washing on two thick wires, I felt a draught blowing into my armpits through the exact spot where my blouse was torn. I didn’t want to repair my clothes because soon, I would begin a journey with my twelve years old daughter. Our final destination: Lampedusa, a tiny Italian island. It was a journey without a visa but full of hope.

Europe. That Europe, where my cousin had prospered, was my last chance, my last dice. The die was cast as I had already paid the men who would shepherd our long journey to Libya and beyond.

I gazed above the clothes that I was hanging and saw my daughter Keita. She didn’t know her father and I would never tell her. He was an uncle who had raped me barely a year after the death of my mother. I had also never known my father.

Like me, this beast of an uncle lived in commune d’Attécoubé. Some called it a shanty but I called it home.

Despite the trauma of my childhood and teenage years, I managed to complete high school and attain a diploma in accounting.

To my shock, my diploma became a source of frustration because it kept reminding me that there were no jobs even for diploma holders like myself. In a plastic folder were 183 copies of job applications that I had submitted.

I felt as useless as the polythene papers that littered our ghetto.

Keita was hungry although she had just eaten a beignet a few minutes earlier. So I gave her money and she dashed to the bakery at the corner for another one.

That evening, we feasted on foufou and gombo sauce. I loved this meal because it was the favourite meal of my late mother whose roots were in Bouaké, the second biggest city of the country.

Inhabitants of Bouaké are known as Baoulé. They are renowned in cotton farming, the region’s main cash crop.

Another wave threw itself into Libya’s hot sand but I didn’t notice it since my thoughts were still in my home country. Would I ever see the splendor of Lake Kossou again? I wondered. This lake was near my rural home and it always calmed my nerves every time I visited it.

‘We are going to live in Europe,’ I had told Keita one morning as she put on her school uniform.

‘France?!’ Her eyes lit up.

‘Yes,’ I nodded happily. The previous day, I had finally accumulated all the money that was needed for us to join the trip.

Apart from my best friend Ninette, no one else knew about the trip as I didn’t want to become a laughing stock in case it backfired.

I watched happily as the small frame of my daughter disappeared though our narrow doorway as she ran to school. Although she was 12, people thought she was 7 or 8. I wanted her to grow up in Europe, far away from the blind life of my country. Blind because one could never see what tomorrow had in store. One never knew if a good education would lead to a good job. Even if you were lucky enough to get a job, the salary was often enough only for your transport, lunch and rent. This meant that you lived for today with no idea of how you would survive if you lost your job or if you fell critically sick. No. I didn’t want my daughter to go through this. I wanted her to live, not just barely survive.

Sometimes, the names of our current and former presidents would trickle into my mind.

Henri Konan Bédié, Laurent Gbagbo, and Alassane Ouattara. Did they care for Keita and I? Just as I wanted the very best for my daughter, did they want the very best for all the children of Côte d'Ivoire? Famous as these names were, the only name that mattered to me was Keita. My beloved daughter.

I just wanted my baby to grow up, study, get a job, get married, get children and be happy. Was that too much too much to ask? It seemed to me that unless she studied well and got a good job; marriage, children and happiness would be beyond her reach.

There was commotion on the crowded beach. Someone shouted something in Arabic. Someone else shouted something in English then finally someone shouted out instructions in French. The boat would arrive soon and we were asked to board it in an orderly way. There would be space for everyone. Remember to pray.

When I had finally left Abidjan the previous week, I had shed tears of joy. I clothed my daughter in new black jeans, new white sneakers, a new green blouse and a new green woolen sweater. After all, a new and better life awaited her in Europe. We joined hands and prayed for the one millionth time.

Then we walked out of our narrow doorway, heavy bags on our shoulders and bubbling hope in our hearts.

I didn’t look behind at the roads of the shanty town of Attécoubé, as if doing so would cause me to change my mind. I was finally walking away from a life of poverty and never ending uncertainties.

Keita and I left Côte d’Ivoire through the small town of Zegoua at the border with Mali. From Mali, we travelled on to Senegal and then Libya.

I will soon be on that boat on my way to Europe. I thought happily as my eyes made contact with the equally joyous eyes look of a Somali woman. Seated at her feet, almost clinging to her, were two kids younger than Keita. Our religions, cultures and countries were different but we were united in our hope for a better tomorrow.

Our lives were in the hands of those men who had taken our money and would now hold our lives in their boat. .

It was time to board the boat.

The Somali woman and I looked at each other once again and our lips parted into half smiles.

In those smiles, was hope for ourselves and our children. My mama used to say that when you lose hope, you stop living.

NOTE:

- 3,149: the number migrants lost lives in 2014 as they attempted to cross the Mediterranean.

- 22,000: the number of people who have perished since 2000.

- 150,000: the number of people who were saved in 2014.

- 36,000: the number of migrants who reached European coasts since January 2015.